As I stagger toward the last official milestone, soon to cross the final frontier between middle age and being a certified old fart, I rejoice about one perk that comes with the turf.

As an older person, I am allowed – and here in Vietnam, encouraged – to moan and groan at younger people about the mess they’re making of this world.

Oh, the sheer joy of being a back-seat driver, meddling in everything yet accountable for nothing!

When issues surface, I just shrug and ask the younger folks how they’re going to fix the mess (i.e. the mess my generation has left them).

In the corner of the world I come from, once you hit 50 or so, you’re transparent, invisible, an apparition roaming around – totally ignored, occupying real estate that others prefer be put to better use.

But in Vietnam, people actually make way for me!

You know those trucks carrying building materials that roar around, drivers sitting on their air horns, forcing all other smaller vehicles to cringe in fear and scurry out of the way like cockroaches when the lights come on?

Believe it or not, one of them actually stopped for me the other day, the driver gallantly gesturing for me to cross the street. I froze, basking in that epic moment, then wobbled across the street.

Per standard Vietnamese road etiquette, anybody stopping for anybody is a miracle, a sight to behold, with the driver’s polite gesture being the absolute pinnacle of respect.

Hot tip: I’ve made a few tests and observed the more helpless you act, the more people will help you.

I remember how my parents recounted horror stories about walking five miles (eight kilometers) in snow up to their butts to get to school, then another five to get back.

They didn’t hesitate to remind us kids of how coddled we were, how many more life options were at our fingertips (couldn’t argue with that one), and generally how entitled and privileged our generation was (no bloody way, we had to fight and scratch for everything).

Fast-forward to life in Vietnam today.

I live near the local university in a neighbourhood with practically no foreign presence, so I end up receiving far more attention than I actually merit. A little bit of rock star status never hurt anyone’s ego, so no complaint from my side.

I’m considered a mentor and role model for students and young grads just entering the working world, as they seek career and life direction. Little do they know my own life has been a mishmash of fate and a hell of a lot of luck, seasoned with a bunch of silly mistakes.

Some of the kids have endless potential and positive energy, so it’s fun to meet them and get their perspective.

I can’t say that about the majority, who are unlikely to start this world on fire, being more inclined to look for shortcuts and easy routes to success, which all us of a certain age know is probably not going to happen.

The same themes emerge over and over again as I meet them:

Most commonly, students request help with their English homework. Most don’t want to learn English; either can’t speak it, or they can but dare not practice (terrified to make a mistake and look foolish, the kiss of death for anyone trying to learn a language), unable to see any value it could hold in this global world.

I routinely bump into said students on our daily rounds, yet instead of asking me in person, they approach me for help on social media.

It took me a while to figure out why they would avoid in-person discussion on this topic, then it dawned on me: They want me to do the homework for them, not helping them as stated, sending this type of message:

Student: “Sir (they always try to boost my ego), can you please help me with my English homework?”

Me: “When’s it due?”

Student: “In two hours.”

Me: “Oh. You probably need to fluff up the planning side while you’re at it.”

Student: “Mumble busy mumble busy mumble mumble.”

Me: “We need to sit down together and go over it.”

Student: No reply, then suddenly a bunch of exercises appear in a message:

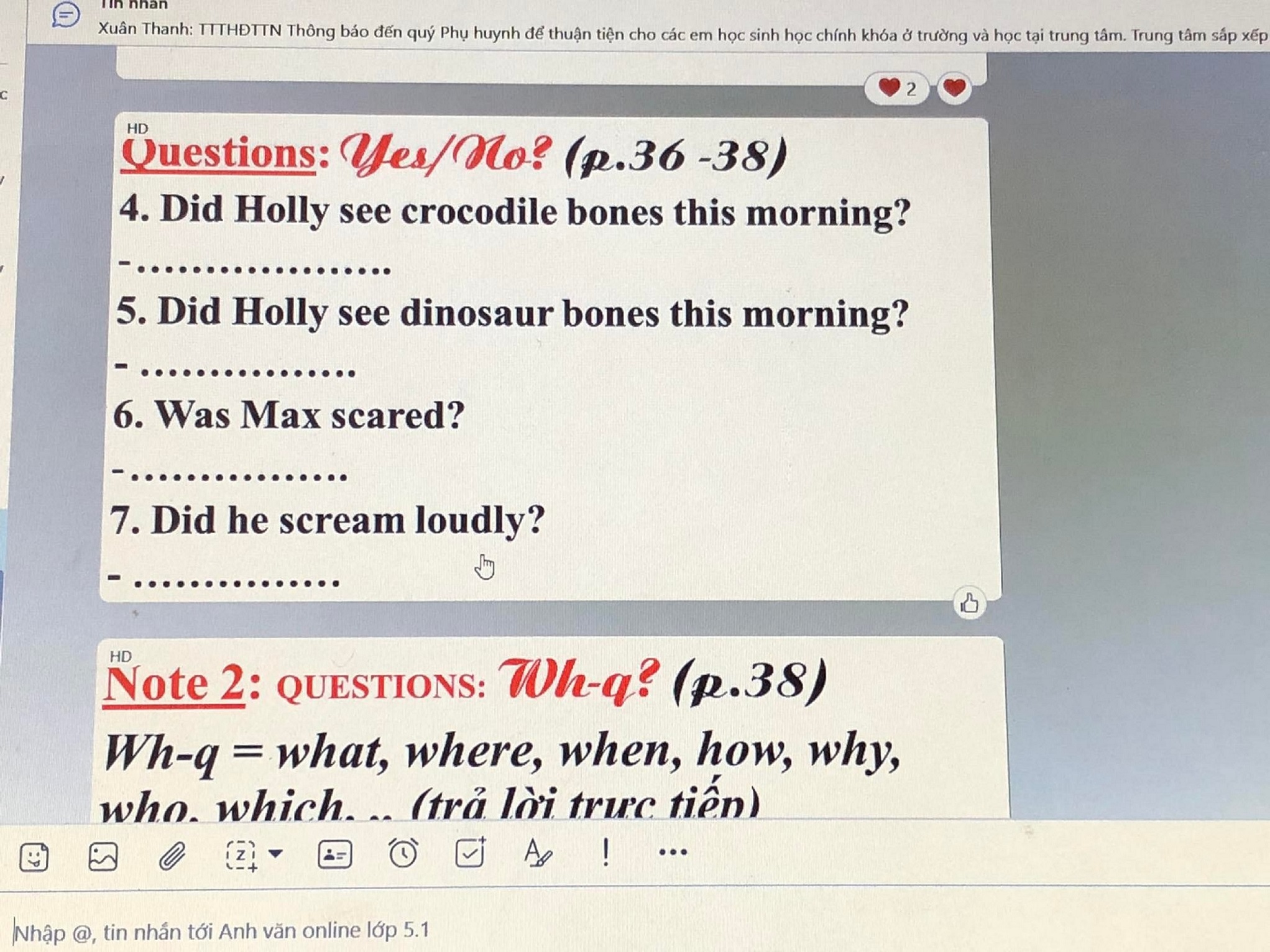

|

|

No wonder English is so unpopular in Vietnam, just look what they’re teaching!

They could be teaching practical daily interactions, such as:

“May I have a cup of kick-arse Vietnamese robusta, please?” Or

“Where is the train station?” Or

“I’d commit cold-blooded murder for a steaming bowl of pho beef soup!”

Some students move on to the second topic – world financial markets. I’m not too interested – those markets are volatile, and, although I’m nowhere near anything remotely close to wealthy, I don’t need the risk.

That attitude has cost me dearly over the years; I vividly recall the Google IPO about 15 years ago where it was priced at US$85 per share.

I scoffed, saying “$85 for a search engine?” (…which was Google’s feature product at that time).

Today it trades at nearly $3,000 per share, its products can zoom in on a freckle half a world away, drive your car while you sit comfortably in back, and probably make a better pot roast than your mom.

That’s a clear testament that I’m not the best person to be giving out investment advice, but I always forge ahead nonetheless, launching into my tutorial about how financial markets function these days.

I explain that not long ago, banks actually used to give us average schlepps money for putting cash in their institutions, then early in this millennium pulled the rug out from under our feet, forcing us to invest in the stock market.

It’s not that the stock market is so great, rather there is no other place to put cash except real estate, which is also famous for its wild gyrations and unpredictable mortgage interest rates, not to mention tax hikes, insurance scams, natural disasters, and the like.

I drone on, pointing out that the banks in Vietnam are still a darn good deal, with fixed-term deposits pulling in a healthy amount of interest with zero risks, although inflation is starting to creep onto the radar.

The stock market in Vietnam just had a banner year, one of the best in the world, but all it takes is one Omicron and the whole thing can fizzle in no time flat.

At that point their eyes gloss over and they start to nod off as they realize the red hot tip – the Holy Grail of “get rich quick” – they sought was not forthcoming.

They think all that’s separating them from a life of hedonistic leisure is one smart move in the money markets. Hell, if it was so easy, the whole world would have already done it, but in reality those diamonds in the rough are rare indeed.

With that setback firmly in hand, they move over to the third topic, cryptocurrencies, the latest rage in the world of investing.

I have no personal experience in that space, aside from awareness that over 90 percent of cryptocurrency is owned by a handful of gazillionaires who got in early. We’ve heard that tune before, so by the time the average Joe gets his hands on it, governments are busy devising tax schemes, restrictions and laws, so the ship has sailed.

These delusions of grandeur aren’t the kids’ fault – their wild dreams are fueled by the propaganda spewed out by media in developed countries, accounts of how hamburger flippers end up roaring around in Maserati cars from one day to the next, having accidentally bumped into a penny stock that went nuts.

Hopefully, those youngsters will pick the right numbers in the national lottery, because otherwise, as friendly and engaging as they are, the chances of fate gifting them a future free of challenge and full of wealth are slim to none.