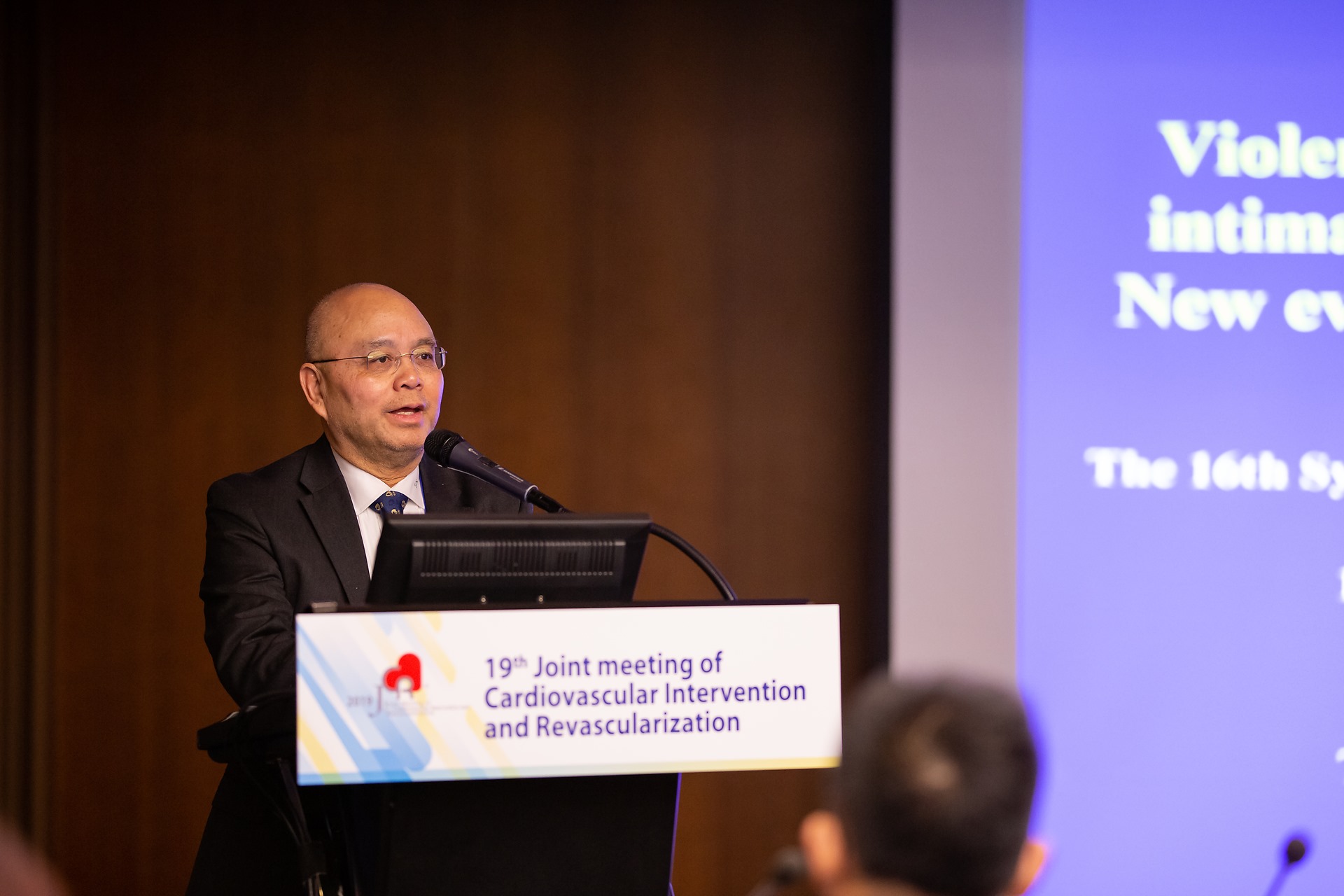

He is also Director of Cardiovascular Research at Methodist Hospital in Merrillville, Indiana.

He has made great contributions to interventional cardiology in Vietnam and the world.

His story is an important part in the journey to Vietnam’s proud position in the field of interventional cardiology.

Why did you decide to go to China to collaborate with American and Chinese cardiologists in 1992? What was the result of the trip?

Between 1985 and 1987, I studied cardiology in New York City and met a lot of Chinese doctors. After returning to China, these doctors became the heads of cardiology departments of many hospitals in Beijing, Shanghai, Xi’an, and Guangzhou. One of them invited my hospital to China to teach a group of local doctors about open heart surgery. This group of doctors performed bypass surgery on the father of Deng Xiaoping’s secretary. In 1992, they invited us to China again to teach angioplasty.

Then a friend of mine, who is the son of a member of the Party Central Committee, asked me why I came to China but did not come to Vietnam. I then decided to go to Vietnam and asked him to help me prepare for the trip. I arrived in Hanoi in 1993 but angiography was not available in the city at the time. I had to wait until 1998, when Prof. Eugene Braunwald – a very famous U.S. doctor at that time – planned to go to China. I asked him if he wanted to come to Hanoi, and he said yes.

The delegation to Vietnam at that time consisted of many famous doctors, including Prof. Michael Gibson – an interventional cardiologist who pioneered the open-artery hypothesis and a leading researcher in the trials of thrombolytics, lipid-lowering drugs, and new medical devices. He was ranked as one of the world’s most highly cited authors in all of science in the past decade by Thomson Reuters in 2014 and has nearly 440,000 followers on Twitter. The delegation also included Prof. Stephen Oesterle from Stanford University, who made many important discoveries for American cardiology at the time.

We were first taken to 108 Hospital, but the infirmary did not have the right conditions for us to carry out new techniques. We were then brought to Bach Mai Hospital, which turned out to be a much more suitable facility. It was just a medium-level hospital then, thus things were deployed and executed quickly without having to go through many levels of consultation. This is similar to the story of Harvard University’s hospital at the time. It was too famous for people to take risks and try something new.

I can still recall the moment when I taught in a hallway that was turned into a classroom at Bach Mai Hospital. Nowadays, the hospital is the leading facility for interventional cardiology in Vietnam and is where the Vietnam National Heart Institute is headquartered. The infirmary is independent in terms of budget, research, and resources, and is not held back by administrative barriers.

How did everything go given the lack of equipment and human resources at the time?

In 1993, Hanoi still lacked a lot, thus we were not able to do anything. By 1997-1998, the capital finally had an angiogram, and that was when we began our work. Dr. Khoi Le gifted us a lot of equipment, which was enough for Bach Mai Hospital’s interventional cardiology department for a year. The support also created favorable conditions for the teaching and learning process.

We adjusted our training program based on the situation in Vietnam back then. The country had lots of cases of mitral valve stenosis. We invited Prof. Ted Feldman, head of the interventional cardiology unit at the University of Chicago, who discovered many new procedures, to teach in our program. He taught the mitral valvuloplasty procedure to Dr. Pham Manh Hung and Dr. Nguyen Quang Tuan.

I asked Prof. Feldman how many cases Vietnamese doctors had to practice on before they could perform the procedure by themselves, and the answer was 20. However, Prof. Feldman did not bring along enough equipment for that many operations. Following two surgeries, Feldman and I began our lecture, while Dr. Nguyen Quang Tuan performed the procedure on a patient and succeeded on his own. We were all extremely surprised and impressed by the ability and spirit of Vietnamese doctors.

|

|

| Prof. Thach Nguyen |

Why was hands-on learning very important during the cooperation of U.S. and Vietnamese doctors in the field of cardiology?

In China, I demonstrated interventional cardiology on television. But how can a doctor know what to do if he just watches the procedure on television? I told my friend, Dr. Dayi Hu, to apply the U.S. technique in the teaching of angioplasty. The trainee will stand next to the patient as the primary operator, while the instructor will stand behind him and provide help when necessary. With this approach, the trainee can learn and improve much faster.

In the past, instructors from the U.S. and Europe often did everything by themselves when they came to China and Vietnam. However, I suggested that the U.S. lecturers apply the hands-on method. The Vietnamese doctors really enjoyed and appreciated this way of learning.

“A doctor once asked me why I am still working. I told him that I have to work to have questions for my scientific research. Asking the correct questions will help me start my research in the right direction. Going to work helps me see the difference between reality and textbooks, find new discoveries, and brainstorm new treatment methods.”

Prof. Thach Nguyen

How do you evaluate the learning capacity of the Vietnamese cardiologists whom you have taught? Whose advancement and success are you most proud of?

In Vietnam, I cooperated with five hospitals, which are mainly in Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City. Many hospitals in Thai Nguyen, Kien Giang, and Can Tho also invited us, but we were unable to go to those places. We thus agreed that it was time for Vietnamese doctors to take over our tasks. Dr. Nguyen Quang Tuan was the first to establish the interventional cardiology program at Thong Nhat Hospital, followed by Dr. Pham Manh Hung with his trips to southern provinces. Dr. Nguyen Lan Hieu, following his study in France and the U.S., further developed the interventional cardiology program in Vietnam and eventually surpassed his teacher. At that time, doctors in the U.S. only performed about 100 surgeries a year at best, while Vietnamese doctors had to take care of 30-40 cases a month due to the high demand for treatment. They worked dozens of shifts a day, thus they progressed very quickly.

Many doctors in Vietnam have achieved very impressive results. Dr. Le Van Truong, head of the Department of Cardiology of the Vietnam Military Medical University, has formed a brand new department, which focuses on angioplasty on the brain to treat patients following a stroke. The development speed and quality of Vietnam’s cardiology were very admirable and astonishing.

I only opened a small door when I came to Vietnam. Prof. Pham Gia Khai, Prof. Pham Nguyen Vinh, and Prof. Dang Van Phuoc have opened up new horizons by sending many Vietnamese doctors abroad. They later returned to Vietnam and utilized what they had acquired to reach their current levels.

How do you evaluate the scientific research capacity of Vietnamese doctors in the field of interventional cardiology?

Vietnamese doctors have performed more surgeries than many other countries in the world. They have done the highest number of mitral valvuloplasty procedures, treated plenty of atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) cases, and performed many angioplasty and high-risk stenting procedures. Vietnam has very high expertise in mitral valvuloplasty, ASD and PDA treatment, angioplasty, and stenting, with many doctors from the U.S., Europe, and Southeast Asia having come to the country to learn more about these techniques. Many famous hospitals in the U.S. have also wanted to send their interns to Vietnam.

However, Vietnamese doctors have not had time to synthesize all the data and publish it in prestigious journals in the world due to a heavy workload.

|

|

| Prof. Thach Nguyen |

You have a lot of innovative and breakthrough research in the field of cardiology, which helps find new ways to improve the intervention of coronary risk. Which study are you most dedicated to and most satisfied with?

I believe it is important to discover a new way to have a detailed look at the morphology, direction, and interaction of coronary blood flow, as it allows us to predict when and where damage will occur as well as understand why the damage occurs at one specific location. Such research is based on hydrodynamics.

In the field of cardiology, a new study, new machine, or new procedure will be obsolete within six months, as medical science changes and evolves very quickly. Therefore, my discoveries prior to 2010 are no longer applicable. We need to perceive this in a practical and humble manner. My book was a best-seller in 2007-2010 but is old-fashioned at the moment and has been replaced by new studies.

This does not happen only to me. Another example is Dr. Ferdinand Kiemeneij, also known as the father of the coronary artery bypass via radial artery, who is an excellent practicing interventional cardiologist based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Many young doctors have become famous and wealthy thanks to his technique. However, he is now just a vague memory.

I would like to share a story. In 2010, Dr. Nguyen Lan Hieu asked me why I no longer returned to Hanoi regularly. I told him that I had already taught all of the best things I knew, thus I had nothing left to offer. There has always been interesting and healthy competition between the young generation and my generation. I have to renew myself so that my way of thinking and working is still meaningful to me, my patients, and the doctors I teach. When a son of a doctor of my generation entered the profession, I looked at him as a colleague, a friend, not a child whom I helped by writing a letter of recommendation for his university scholarship. The young doctors who worked with me in the past have become very successful people, holding important positions in many leading healthcare units.

My latest research is about hydrodynamics in cardiology, aimed at tracing the causes of cardiovascular diseases. I want to present the data of the research in Vietnam first so that if the study is able to help global cardiologists change their treatment methods, Vietnam will be recognized as the first place where this new study is published.

In a speech to medical students as they began their medical path, you welcomed them on a special journey to discover the human body and mind, as well as to protect human life. You also emphasized that doctors, as medical scientists, not only need to come up with treatment solutions, but also have to join the fight against many social stereotypes and bad habits. Which experience in your career did the advice come from?

Working in the medical industry is not just about money, although the money coming from this profession is honorable. By becoming a medical practitioner, one must fulfill the duty for the sake of patients and the society as a whole. Practicing medicine is fulfilling the duty and caring for other fellow human beings in the best possible way, with all of the acquired knowledge and empathy between people. That is what makes a doctor different from a treatment machine.

I wish all Vietnamese doctors bear in mind the paramount maxim in medicine: “Primum non nocere,” which means “first, do no harm.” A doctor is not just about expertise, but has to be free in thinking and acting. A doctor has to be brave to walk beyond obsolete paths and overcome stereotypes in order to seek and protect the truth.

In the U.S. and the world, many famous figures in medicine were both medical and social activists. Aside from being able to execute treatment procedures proficiently, a doctor must make sure their patients can lead a healthy and happy life. This is why I always emphasize comprehensive care when I teach young doctors.

Another significant aspect is preventive medicine, as it summarizes biological laws for each individual and each population to indicate the respective health risks.

Preventive medicine is the root and foundation in bringing benefits to people, while interventional medicine is the fruit that can help individuals with severe illnesses. Preventive medicine is the most effective and economical way to take care of people’s health. Preventive medicine requires doctors to have extensive knowledge in other fields.

In patient care, doctors do not just treat the disease. Once the patient gets sick, it is too late. In order to best serve the society, a medical practitioner needs to help their patients prevent illnesses.

|

|

| In 2007, Prof. Thach Nguyen’s second clinical book – Practical Handbook of Advanced Interventional Cardiology – was considered as a compass for cardiologists worldwide, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, American Journal of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, and an Italian journal. The book was published for the first time in 2000 and the second time in 2007. The Internet was not yet popular at the time, so many cardiologists read the book to improve their knowledge. It was published for the fifth time in 2018 but did not sell as well as in the past. |

You once said that doctors need to focus more on making decisions that are in the best interest of their patients, including giving the most suitable and economical treatment. Why did you give that advice? What should Vietnam do to reduce treatment cost while maintaining the growth of its cardiology sector?

Vietnam is not the only country that is facing high treatment costs. The U.S. also has a similar situation. If patients do not know how to prevent diseases, the cost of treatment will be so high that neither Vietnam nor the U.S. is able to keep up. Therefore, prevention is the best way to alleviate diseases and reduce treatment cost. Doctors will not fulfill their missions if they fail to provide patients with guidance on disease prevention.

In cardiology, there are many ways to educate patients on how to prevent diseases, such as talking and explaining, requiring them to give up smoking and drinking, and advising them to have a low-salt and low-fat diet and perform regular exercise. About 10 percent of patients will not listen to these instructions, but doctors must keep advising them, because it is their duty.

The next thing I want to talk about is medicine. My book was a best-seller because it addressed this topic in a practical manner. If patients cannot afford the prescribed medication, doctors must help them pick out the most important medicine in the prescription, before adding the second and third most important drugs depending on the patients’ financial capacity. The best treatment plan has to be in the best interest of each patient. When making a prescription, doctors must take into consideration their patients’ circumstances and living conditions. Doctors must also make sure patients do not miss doses and know how to properly store medicine and dispose of expired drugs.

For example, it would be bad if a doctor places a stent in a patient and does not check up on him following the procedure. Doctors must perform regular follow-ups to help patients prevent diseases and improve their health in a sustainable way. In patient care, doctors must offer the best, simplest, and most affordable solution to their patients. Otherwise, it will be difficult to lower treatment costs.

Is there any particular story in your medical career that you would like to share with readers?

I would like to talk about Prof. Pham Gia Khai. At the beginning of the cooperation program, there were quite a lot of conservative colleagues. However, Prof. Khai always tried to defend young doctors and create opportunities for them to learn and practice risky procedures. I really appreciated him for that.

Between 1990 and 2000, senior Vietnamese officials often had to go to China and Singapore to seek treatment for their health conditions. Following this period, Vietnamese doctors were completely capable of providing such treatment because they had had a chance to learn and practice. Vietnamese doctors have worked with great social responsibility. They not only cared for important figures in the society, but also provided treatment to every other citizen. That is the true meaning of medicine, as all lives are equal.

Thank you very much, professor!

|

|

| Prof. Thach Nguyen (L) and Prof. Eugene Braunwald (Harvard University) |

Medical bridge

“In 1997, Vietnam’s medical industry did not have many opportunities to interact with advanced medical fields. Prof. Thach Nguyen acted as a ‘bridge’ by inviting delegations of professors and doctors from the U.S. to Vietnam to organize seminars and share their knowledge and experience. That was the first time I met Prof. Thach Nguyen and worked with him until the present.

What makes me admire and appreciate Prof. Thach Nguyen are his dedication and devotion for the generation of young Vietnamese doctors. Thanks to him, many generations of young doctors have had the opportunity to study, do research, and be exposed to the most advanced medical science in the world over the past years. More than 200 young doctors have been given the chance to study in the U.S..

The professor has also had many initiatives in medical research, and his study of hemodynamics in the heart has offered many practical values. He is among the few Vietnamese scientists who have cooperated with leading scientists in the world to co-author and publish many valuable medical books.”

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pham Nguyen Vinh (director of Cardiovascular Center of Tam Anh Hospital, vice-president of the Vietnam Heart Association)

Sky is the limit

“Vietnam’s interventional cardiology has grown a lot, and all of the new techniques can be performed in the country. On August 2, Vietnamese doctors continued to discuss online with Dr. Michael Gibson from Harvard Medical School, who is also CEO of the Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute). On October 24, the Vietnam Society of Interventional Cardiology, chaired by Assoc. Prof. Ho Thuong Dung, will organize a webinar on the latest interventional technique – using shock waves to disrupt calcium plaque in the coronary arteries.

I brought interventional cardiology to Vietnam, but young doctors are the ones who have developed and brought the interventional cardiology program in the country to its current level. They are Assoc. Prof. Nguyen Quang Tuan, Assoc. Prof. Pham Manh Hung, Assoc. Prof. Pham Nhu Hung, Assoc. Prof. Nguyen Lan Hieu, Dr. Nguyen Thuong Nghia, Assoc. Prof. Ho Thuong Dung, Assoc. Prof. Vo Thanh Nhan, Assoc. Prof. Truong Quang Binh, Dr. Pham Quoc Khanh, Dr. Tran Van Dong, Dr. Do Quang Huan, Dr. Nguyen Cuu Loi, Dr. Ton That Minh, Dr. Dinh Duc Huy, and many others. The Vietnamese interventional cardiology community has been very good at adopting and using equipment and techniques developed in other countries. Now is the time for them to develop new treatment methods, invent new devices, and introduce them to the world. In medical research and application, the sky is the limit.”

Prof. Thach Nguyen

An endless source of energy and inspiration

“In 1996, Prof. Thach invited a group of leading professors from the U.S. to provide hands-on training at our institute,” said Assoc. Prof. Pham Manh Hung, director of the Vietnam National Heart Institute.

“It was very rare as other countries did not provide such training. We usually had to come to other countries and study at their hospitals. Those first lessons were very valuable as they greatly changed the face of Vietnam’s interventional cardiology.”

Aside from the techniques that Vietnamese doctors learned and applied, the medical supplies that Prof. Thach Nguyen brought to the country also contributed to the positive changes.

“A lot of patients suffered mitral valve stenosis at the time, so we really wanted to treat them with the balloon mitral valvuloplasty procedure. Prof. Thach invited the ‘father’ of this technique to guide us in the first five operations. After that, Vietnamese doctors were able to perform the technique on their own. I was very emotional that day. Prof. Feldman said he was confident that we could do it, and we indeed did a really good job,” Assoc. Prof. Hung recalled.

Prof. Thach Nguyen also assisted young Vietnamese doctors in completing another important task, which is presenting their research to the medical community. Thanks to his support, the Vietnam National Heart Institute was eventually selected to demonstrate an operation during an international cardiology conference.

“At the 2008 Southeast Asian Cardiology Conference, we were very nervous, as it was the first time Vietnam had become the host of an important professional conference that was attended by many international colleagues. Along with reports from Vietnamese and regional doctors, Prof. Thach also invited famous doctors from many countries to present their techniques. The conference was a great success, attracting more than 3,000 doctors, professors, and cardiologists,” Assoc. Prof. Hung said.

“We are following in the footsteps of Prof. Thach,” he continued.

“During a trip to Quang Ninh Province General Hospital of former Minister of Health Nguyen Thi Kim Tien, many patients said they were happy that they no longer had to travel to Hanoi to seek treatment, after doctors in the northern province were able to applied many cardiovascular treatment techniques, including interventional cardiology. The result was only achieved after accomplished Vietnamese doctors came to lower-level hospitals and provide local colleagues with hands-on training, just like how Prof. Thach helped them in the past. I learned from Prof. Thach two key things – changing academic thinking and inspiring young doctors. Nowadays. Vietnamese cardiologist have been mentioned in international books, performed surgeries in many countries, and shared their experience to overseas colleagues, all thanks to the first foundations laid by Prof. Thach.”

Assoc. Prof. Hung believed it is important to continue on this path. He hoped that Vietnam will have more outstanding cardiologists, as the number of people with cardiovascular diseases in the country is still high. Up to 200,000 Vietnamese people die from cardiovascular diseases a year, twice the number of people dying from cancer. More cases have also been recorded among young people.