“Because of the pandemic, I could not work for many days, so my resources dried up. Thanks to 100 eggs and a bag of flour I had received from a person, I tried to sell fried rice flour cakes again, hoping to make ends meet,” recalls Nam, a woman who has worked as a street vendor in Ho Chi Minh City for more than 30 years.

The disastrous encounter was unprecedented for her in those decades.

Many vendors never come back

Indeed, Nam’s demanding situation is not uncommon. According to a survey conducted by Social Life and Oxfam in Vietnam, more than 60 percent of street vendors in Vietnam face a lack of capital due to the prolonged pandemic.

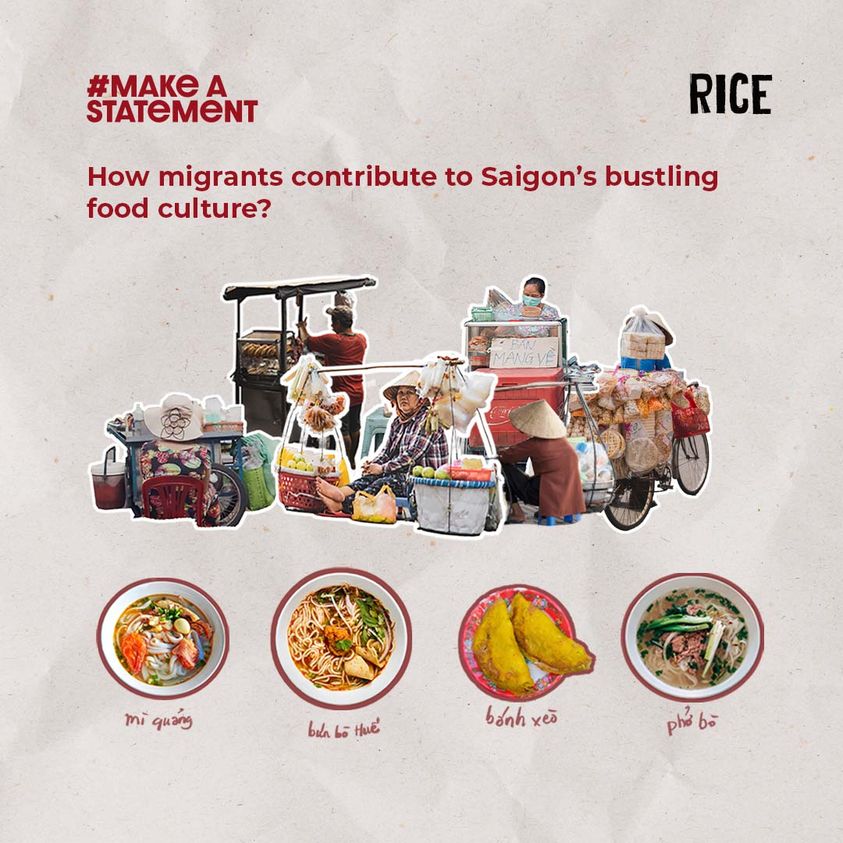

Despite generating more than 13 percent of the city’s gross domestic product (GDP), street vendors, sometimes considered informal workers, have faced many difficulties since the COVID- 19 pandemic broke out in Vietnam in 2020.

Even though the restrictions associated with COVID-19 have been lifted, no one can say for sure how many stalls have reopened and how many street vendors will never return.

Moreover, as eaters, we cannot know what stories lie behind the smiles of the street vendors we encounter every day.

More importantly, are there things we can do to help them? Are there ways we can offer to help street vendors return to their familiar working environment and become an integral part of the city life as they have been for a long time.

These were some of the questions raised in the talk show titled “Ẩm thực đường phố, ngồi xuống kể nghe!” (Street food, please sit down and let us tell).

The show was co-hosted by Dear Our community and RICE Content, Media, Oxfam, Social Life Research Institute and Sai Gon Um Company Ltd.

Increasing vulnerability

Let’s get back to Nam, the street vendor from the first part of the article.

She first came to Ho Chi Minh City to work when she was 27 years old and had two children. At the time, she never imagined that her life would be attached to the city for this long.

The woman worked hand-to-mouth in the city for 11 years as an assistant at a stand selling sugar cane juice, learning the secrets of mixing the drink from a friendly male street vendor. She also sold fried rice flour cakes with scotch eggs twice a day.

Selling the Chinese-influenced snack helped Nam raise her children. They grew up and she has already become a grandmother thanks to the stand.

Unfortunately, her life and work were turned upside down when the pandemic broke out.

The disease devastated street vendors like Nam. The impact was worst for vendors who depend on familiar customers and are unfamiliar with food-sharing apps or platforms.

According to Dr. Nguyen Duc Loc, head of the Social Life Research Institute, most street vendors work “hand-to-mouth” with their income being just enough to cover expenses.

Despite limited resources, it is often enough for people to start a family. In another way, the amount of money shows the spirit and determination of immigrants.

According to Duc Loc, the migrant workers do not expect to receive more monetary donations.

They just hope that the pandemic will soon phase out and they will find a way to reopen their stalls. As independent workers, they are used to living on their own and are willing to help others in the same situation.

“Their ‘capital’ for business is their own lives,” Loc says, adding that their experience and skills have contributed to Ho Ci Minh City’s flexibility, openness, and generosity.

However, there are many customer behaviors that have changed during the ongoing pandemic.

The street vendors like Nam (vendors who do not know how to take advantage of technology in their work) are compared to leaves lying on the street, vulnerable to changing winds.

They are workers who need more help than others given this vulnerability.

Offering a path to the future

“When I look at the markets, the areas of the stalls that once attracted so many customers and were rated by famous international broadcasters, it makes me so sad,” chef Nickie Tran, owner of the Kau Ba Quan restaurant chain, shared his thoughts.

“The beauty of street food is not in an app to order the food to be conveniently served on the spot, but in special street vendors like Nam,” added the man, who is also the administrator of the food review group Saigon Um on Facebook with more than 800,000 members.

As for Nickie Tran, vendors like Nam are different from others in their friendliness to customers. They are vendors who are willing to keep a tab for diners if they forget to bring money, give a discount, or even give food for free when they meet a person in need.

“Street food is a beauty of Saigon. If it were not for these street vendors, Saigon would not be the Saigon city it used to be,” Nickie Tran said.

Nickie Tran shared how the Saigon Um group has worked so far. He said his community group often looks for street vendors like Nam and young entrepreneurs who open a local food business to author reports about their products.

“Our members not only write about food, but also share memories and stories about the city’s residents, who help create the beauty of culinary street food experiences in the city,” Nickie Tran told Tuoi Tre (Youth) newspaper.

The administrator of Saigon Um is proud of his group’s non-profit work and of being a trusted food news source for the public.

However, he also admitted that his group has not done much to help street vendors, especially in this difficult period.

Nickie Tran hoped the vendors will also be treated more equally.

“They do not depend on the city, nor do they make the city uglier. On the contrary, they contribute both physical and spiritual values to society. It is more important that we make plans for street food with a kinder and more loving approach,” he added.

Dr. Nguyen Duc Loc suggested, “We need more practical projects starting from different resources.”

According to Loc, who has been working as a researcher and consultant on projects to solve social problems in Vietnam since 2004, especially those affecting disadvantaged groups, the youth can give a helping hand to vendors who have limited ability to use technology.

“Vendors like Nam have great difficulty adapting to food apps or platforms, but young people can help them. Let us “sell” street food stories to tourists as an interesting feature,” suggested Nguyen Duc Loc.

“While many products need stories to be promoted, street food already has its own stories. It is our job to pay attention to them, listen carefully and bring them to the public,” he added.

Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter to get the latest news about Vietnam!